Note: These website pages contain the official published version of Understanding and Managing Flood Risk: A Guide for Elected Officials. Printable .pdf versions are available at the following links: Volume I: The Essentials, Volume II: Moving Beyond the Essentials, Volume III: Success Stories. Please note that this website may be edited in the future with additional updated content but there is no plan to update the .pdf versions produced in February 2020.

Note: These website pages contain the official published version of Understanding and Managing Flood Risk: A Guide for Elected Officials. Printable .pdf versions are available at the following links: Volume I: The Essentials, Volume II: Moving Beyond the Essentials, Volume III: Success Stories. Please note that this website may be edited in the future with additional updated content but there is no plan to update the .pdf versions produced in February 2020.

Section A. Flooding and Flood Risk in Your Community

Your community's exposure to flood risk is probably different from other communities in your state. Understanding the vulnerability of your citizens and your built environment – homes, businesses, public buildings, parks, and infrastructure – is an important first step in working to minimize damage and impacts from the next flood.

Just as valuable is to identify and understand how undeveloped land is affected by flooding, so your community can decide how best to guide new development or redevelopment in those at-risk areas.

In Volume II: Moving Beyond the Essentials, you'll learn the basic concepts of floodplain management, flood insurance, your community's responsibilities, and opportunities to reduce flood risk.

1. Where do I start?

A good first step is to ask your floodplain manager to help you collect local and historical flood facts. Check your local hazard mitigation plan (described in Question 8), ask staff in your planning, public works and roads departments, and talk to the emergency manager. Your professional staff is your primary source to learn about your community's flood risk:

- Someone on staff is designated as the floodplain manager (sometimes called the floodplain administrator). This designation was made when your community joined the National Flood Insurance Program and probably is identified in your floodplain management regulations (see Question 38 about establishing and managing your floodplain management program).

- Staff in public works, engineering and utilities departments (or regional planning and drainage district personnel) may be aware of problem areas, especially areas subject to frequent flooding that aren't shown on flood maps.

- The local emergency manager can tell you about past flooding and whether existing emergency plans identify evacuation areas.

Prepare yourself with the answers to questions such as:

- How many buildings were damaged or destroyed by the last flood?

- Was anyone injured or killed by the flooding? What were the circumstances?

- How many businesses were flooded? How long did it take them to recover? Were any unable to reopen? How were employees affected?

- Were roads flooded? Bridges and culverts damaged or washed out?

- How many buildings in the floodplain were not damaged and was that because they are elevated?

- How many owners of damaged buildings were insured? Not insured?

- What was the impact on local government? Were critical facilities or other government-owned structures such as schools impacted? Were important resources unavailable?

- Were renters insured? Did they understand the importance of having flood insurance coverage for personal property?

- What was the average flood insurance claim payment? Do we have properties that have received multiple claims (sometimes called "repetitive loss properties")?

- Was there mold, mosquitoes, unsafe drinking water, debris or hazardous materials released that caused secondary health threats or problems?

- Have natural systems, such as wetlands that can absorb flooding, been impaired over time, leading to more flooding?

- Has there been a lot of development in the watershed above your community? Are downstream areas experiencing flooding more frequently, perhaps caused by the additional runoff from paved surfaces and buildings?

- Have grant programs or other financial incentives been used in the past to alter flood risk through property acquisition, elevation, or other forms of mitigation? Are any projects ongoing or contemplated?

2. How do I learn more about my community's flood risk?

Another great source of information about your community's flood hazard and risks is your hazard mitigation plan (see Question 8). Many communities develop these plans on their own or participate in multi-jurisdictional plans. These long-term strategies identify natural hazards and assess the potential impacts of those hazards. Importantly, the plans lay out risk reduction priorities, assess the capability to act, set an action plan for risk reduction, and form the basis of requests for mitigation grant funding. (Some grant programs are described in Question 10.)

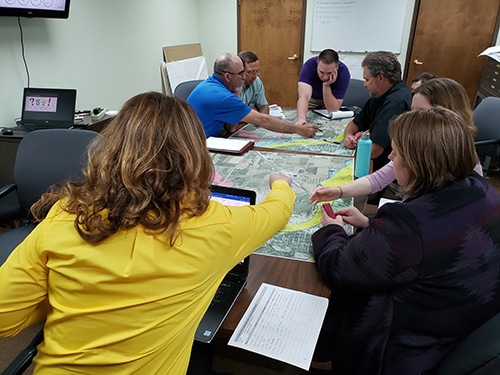

Get involved in your community hazard mitigation plan process.

Ask your floodplain administrator, community planner, or emergency manager to show you how to access your community's hazard mitigation plan and when the next revision is scheduled. Governing bodies must formally adopt mitigation plans and each subsequent revision of the plans, which typically occurs every 5 years. You may want to participate in the next revision to better understand how actions are prioritized.

Hazard mitigation plans include descriptions of the impacts and overall vulnerabilities for each identified hazard. For flood hazards, this often involves overlaying flood hazard data onto property tax maps or other maps that show building locations. The results can be summarized at the community level, or down to the neighborhood and business district levels. Mitigation plans must also list the number and type of repetitively flooded properties, which is another indicator of flooding challenges. Reviewing maps in the mitigation plan, along with any information on the number and types of buildings at risk, gives you a good picture of your community's risk. Overlaying flood maps onto topographic (ground contour) maps allows you to identify where floodwater will be deep or shallow.

3. Why should I know which areas of my community may flood?

When you know which areas are shown as flood-prone on flood maps and which areas have experienced flooding (even if not shown on flood maps), your community is better prepared to:

- Regulate and guide new development to minimize risk (see Section G)

- Communicate risks to your citizens (see Section C)

- Plan for evacuations of people before the onset of flooding, mobilize resources to aid in rescues during flooding, plan to meet sheltering needs, and preposition recovery resources

- Identify public buildings and facilities, including bridges and culverts, that might be impacted, interrupting public services

- Consider and plan for recovery and redevelopment after damaging floods (see Section B)

- Identify opportunities to mitigate flood impacts (see Section B)

Flood risk isn't just about which areas might flood and how high might floodwater rise. Understanding the expected duration of flood events also informs community decisions and actions. Long-duration flooding that lasts days or several weeks creates different demands for shelters and housing than short-duration events that may last a few hours or just one or two tide cycles. Similarly, long-duration flooding may prevent access to some neighborhoods and may mean utility providers have to shut down water and sewer services.

It's easy to find and print your Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) online.

See the Flood Insurance Study and all FIRMs for your community by visiting the FEMA Flood Map Service Center and click on <Search All Products.> Follow the instructions and select your state, county, and community. You may view, print and download flood maps, open an interactive flood map (if available) and view all studies and maps for your community. For more help, call 1-877-FEMA MAP.

To make a snapshot of a specific area, called a FIRMette, visit the same website and click on <Search by Address.> Then type in an address and search. You'll need to zoom in and pan around the map to find the area of interest. Then follow the instructions to make a FIRMette. Learn more by downloading the tutorial "How to Print a FIRMette and Download a FIRM Panel."

4. What about my community's publicly owned buildings?

An often-overlooked element of flood risk is a community's own buildings. The first step, determining whether publicly owned buildings are vulnerable to flooding, may have been done as part of your community's hazard mitigation plan (see Question 8). That step involves reviewing the FIRM to see if publicly owned buildings are in or near the mapped floodplain. Then you can work closely with your local floodplain managers, engineers and risk management advisors to determine if further action is required. Questions to ask include:

- What depth of flooding around the building can be expected during flood events? What is the possible range of outcomes for different scenarios (1% annual-chance flood; 0.2% annual-chance flood)? Could floodwater get into the building? Has the building flooded before? Do we have data to support an estimate of damage costs if the building is flooded in the future?

- What is the required warning/evacuation time for staff and occupants? Are there safe access and egress routes to the building? Do first responders use the building during flood emergencies?

- Are there important documents, high-value equipment, historic artifacts or other irreplaceable items located in areas that could flood?

- What options do we have to keep water out of the building?

- Has the building been dry-floodproofed? If yes, do staff know about procedures for protection? Are the materials to implement dry floodproofing easily accessible? Has flood preparation been rehearsed?

Flood prone public buildings

Most communities with public buildings located in mapped floodplains are not aware of a significant consequence if those buildings are not insured for flood damage. If damaged by a flood event that is declared a major disaster, FEMA may withhold public assistance that would otherwise be available, in amounts up to $500,000 on structural damage and $500,000 on contents damage. Can your community afford what is equivalent to a $1 million deductible – for each flood prone public building?

Another critical aspect of risk management when public buildings are in mapped floodplains is insurance.

- Does your community's coverage through municipal insurance pools cover flood damage?

- Does the municipal insurance pool expect flood-prone buildings to be insured under the NFIP?

- If a building is not adequately insured for flood damage, what's the likely cost of repairs if flooding occurs?

- If insured with an NFIP policy, does the policy have enough coverage on the structure and contents (see Question 32 about flood insurance coverage)?

5. What are the economic benefits & costs for reducing flood risk?

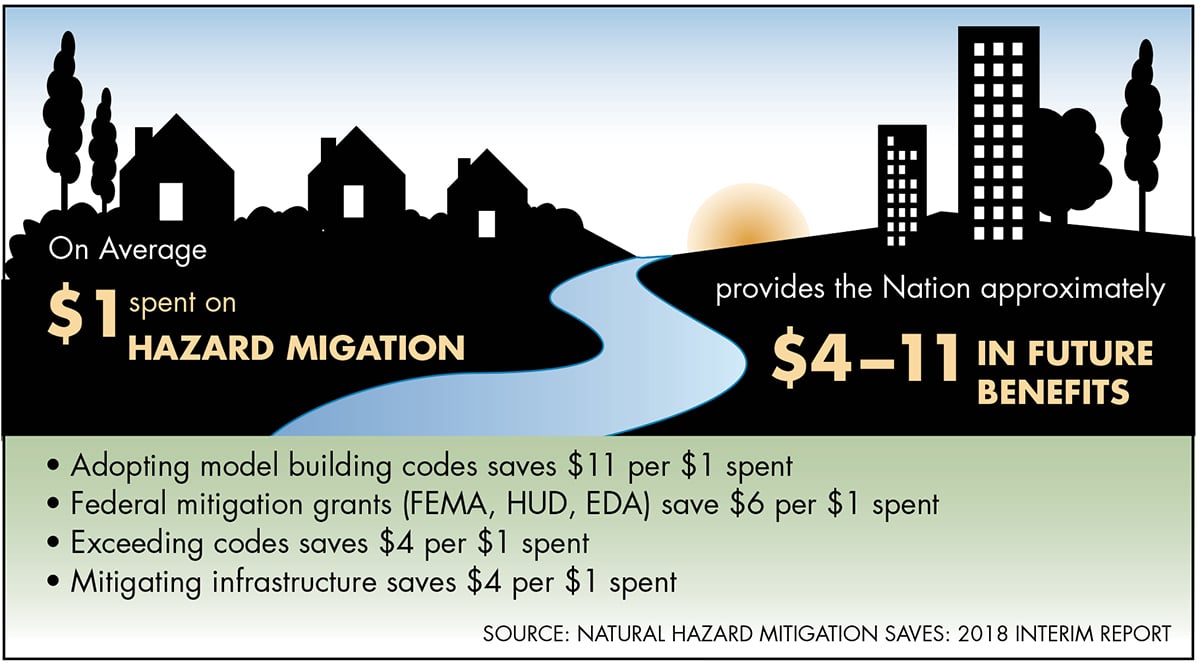

For elected officials, the cost of flood mitigation can be a significant political issue. Constituents are often concerned about the upfront cost, and they may not fully appreciate future savings due to damage and costs avoided. Although flood mitigation saves money in the long term, the exact amount is often difficult to quantify. For this reason, many risk reduction savings are either not monetized or aren't factored into the bottom line for budget considerations. For some, mitigation can look like an expense rather than a savings or investment. That said, when the full benefits of hazard mitigation are identified, taxpayers and elected officials can come together to assist those in need and reduce off-budget taxpayer spending after future disasters.

The economic impacts of floods on individuals and property owners include lost wages (or job loss), lack of transportation, expenses for evacuation (temporary housing), and significant physical and mental health issues before, during and after flooding. Businesses are affected due to lost productivity as employees may be unable to get to work when roads are flooded or washed out, or because they are focused on repairing damage to their homes. Impacts may be widespread when flooding shuts down utility networks.

Impacts to Small Business

According to FEMA's 2015 Business Infographic, almost "40-60 percent of small businesses never reopen their doors following a disaster," and another 25 percent fail within one year. Similar statistics from the U.S. Small Business Administration indicate that over 90 percent of businesses fail within two years after being struck by a disaster.

Communities suffer overall as a result of flood damage. Local funds earmarked for other uses must instead go toward flood repair and recovery, and community resources (staff, equipment and infrastructure) must be focused on response and rescue, which also puts responders and utility workers at risk for injury and/or loss of life. Community infrastructure can be severely impacted, including the costliest elements such as water and wastewater treatment facilities and roads and bridges. Debris collection and landfill disposal, and other environmental cleanup, can be significant. The combined impacts on businesses, individuals and communities reduce local tax revenue (income, property, employment, etc.) in both the short and long term.

A major issue with flood risk is that the costs and benefits are borne by different parties; this is what economists call an "externality problem." Builders and local governments may reap the benefits of developing in risky areas, but they do not incur all the future costs when homeowners must buy flood insurance and when homes are flooded. Instead, many of the costs fall on property owners, and often, the general taxpayer through disaster assistance programs.

Success Story Connection – Past Investments Saved Money

The Left Hand Creek Flood Project saved Longmont, Colorado an estimated $22 million in losses avoided in the 2013 flood. "If we had not done that project, there would have been another thousand homes flooded," said Dennis Coombs, former mayor of Longmont.

Seeing the benefits of investing in cost-effective flood mitigation may require a change in thinking. It is economically beneficial and will result in long-term community resilience to shift toward flood mitigation measures, and away from simply recovering or "getting back to normal" after floods. Mitigation in general, and nonstructural measures in particular, tend to be more cost-effective and sustainable long-term solutions than structural measures. Nonstructural measures include land-use planning and zoning, floodplain restoration and elevating or removing property from harm's way. Structural measures include using levees, floodwalls and dams.

Nonstructural mitigation measures often have benefits beyond flood risk reduction and protection of public safety. Such measures can revitalize urban neighborhoods, improve the environment (primarily water quality), enhance or expand public spaces, and increase economic development (improving property values). According to a report by the National Institute of Building Sciences, the economic benefits of hazard mitigation outweigh the costs by four to one (some research indicates the ratio is as high as five to one). The benefits of individual projects may vary.

Benefits of Open Space Recognized by the NFIP Community Rating System (CRS)

The NFIP Community Rating System, described in Question 43, rewards communities that administer floodplain management programs that go above and beyond the minimum standards of the NFIP. In a 2013 study, savings associated with a one point increase in CRS credit under Activity 420 (Open Space Preservation) were estimated to average $3,532 per community per year.